Welcome to Part III of this free, user-structured writing course.

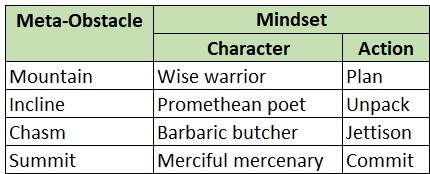

The overarching course theory is provided in Part 0. To summarise, the challenge of writing is similar mentally to mountain climbing. You can improve your writing by contemplating certain mindsets, and playing their characteristics against the metamorphic/metaphoric mountain:

In the first two parts of this course, we focused on the first two rows of the table. The wise warrior character can survey an entire mountain of a writing task, and plan how he will live while climbing. The Promethean poet can face a sheer incline of a blank document, and unpack her ideas systematically before it. We know from real mountains that inclines are never just upward – sudden chasms perforate the mountainside. Now then, we turn our focus to row three: Chasm, Barbaric butcher, Jettison.

The writer’s chasm

The writer’s incline and chasm are a duality, like yang and yin in the naturalist and alchemic schools of ancient Chinese philosophy. Incline (yang) is additive, in that you must unpack and scribe a framework of ideas, then add nuance to it, until you are satisfied you have a completed text. Nonetheless, there is a subtractive element to the process at a finer scale, as you chip away at information, deciding which elements should be kept or discarded.

Chasm (yin) is the nightside of incline, and therefore is subtractive on the whole yet additive at finer scales. This meta-obstacle is the collective pitfalls of writing – writer’s block, procrastination, perfectionism, imposter syndrome, tangential pontification, alcoholism – whatever grabs you.

We sometimes need to create unreal monsters and bogies to stand in for all the things we fear in our real lives.

— Stephen King, ‘The Shining’, 1977.

Fundamentally, the chasm is any point when the writer realises their text is too cumbersome. All too often I ‘finish’ writing, and as I read through, I realise that there are too many ideas in the mix. This mountaineer model of writing is an apt example. Initially, I set out to describe my theory in one post. As the wise warrior, I planned my life around the climb foreboding, and as the Promethean poet, I unpacked and elaborated upon all the ideas I deemed relevant to the story corpus. I was not prepared for the chasm; the sudden realisation that my ideas were undercooked so close together. Thus I became the barbaric butcher, and cleaved the text into four rough cuts plus an overview. Within each piece, I trimmed and discarded as much of the fat as I could.

Literary chasms can be disastrous to the fate of any text. Some writers miss seeing them altoghether, and plummet under the weight of the myxomatoxic ideas they’re so curious to chase! If you find yourself in such a predicament, give yourself a pat on the back, because too many writers waste time in denial of this plane of existence. How to escape it – or even better, how to avoid – is the barbaric butcher’s special talent.

It is my ambition to say in ten sentences what others say in a whole book.

— Friedrich Nietzsche, ‘Twilight of the Idols, or, How to Philosophise with a Hammer’, 1888.

The writer’s mindset

Character

The literary butcher mindset is barbarous. Once you think you have planned and built a solid essay, you must be prepared to tear it apart with savage abandon. What you will find is that your penultimate draft has good parts – the meat and vegies – and bad parts – the fat. (Gravy comes later – see Part IV.) As a barbaric butcher, your job is to severe good from bad, retaining as much of the former as possible.

How does this relate to mountaineering? The key linking phrase is ‘survival of the fittest.’ A party of mountain climbers work best when working together, but each individual does so on the cold understanding that in crises, only the strongest will survive.

Consider the case of Green Boots, an unidentified Everest climber, and one of many hundreds who died near the summit and remains there to this day. In 2006, a party of 18 mountaineers came across a British climber, David Sharp, who was suffering from hypothermia in Green Boots’ cave. Russel Brice radioed in from base camp, and instructed the party to continue their descent, leaving David to die next to Green Boots.

There is no consensus on the morality of this decision. Some agree with Brice et al., that it is not worth jeopardising the survival of an otherwise healthy group of individuals, by attempting to save an extremely ill individual. Others argue that Brice et al. could have revived Sharp with bottled oxygen and gotten him back to safety, without taking more risks than they would’ve been taking anyway.

Thankfully, the physical act of writing is not life-threatening, to either the writer or to other people. In the writing sense, the barbaric butcher is concerned with ‘survival of the fittest ideas’, rather than ‘survival of the fittest humans in a risky situation’. Nevertheless, he must be, like the mountain climber, brutal in committing to his choices.

A climber facing a chasm must decide how to proceed so as to maximise his or her survival chances. Often, it is pragmatic to jettison stuff that is no longer needed into the chasm. Indeed, the caverns and crevasses of Mt Everest are littered with tonnes of discarded supplies. One set of climbing notes mentioned that a team “…was nearly hit by oxygen cylinders jettisoned down the north face by climbers making their summit bid on the classic North Ridge route.”

A writer facing a chasm must also decide what to move on from, but this time we’re talking about ideas, not vital supplies or a fellow climber’s body. The temptation that many writer’s face is to carry every idea in text, but this never works; their collective weight will either drive the writer mad, or bore the reader silly.

The trick to avoiding a Carollian rabbit hole is preparing to jettison at least some of your ideas, even if they’re good ones. To that end, the mindset of the barbaric butcher is helpful. Regardless of the overall quality of meat he is cutting – there is no such thing as the perfect leg of lamb – the butcher decides unflinchingly what gets the chop versus what is retained for market. Below, I propose a few guiding actions that you can take whenever you are not sure how to finish telling your story.

Action

Jettison excess venison

I can’t say it better than William Strunk, Jr. and E. B. White: “Omit needless words.” Whatever you jettison need not be lost, either; copy and paste it into an offcuts document, or summarise the idea in your research diary for later referral.

Venison is a choice cut of meat, and so, to jettison excess amounts of it implies that you can have too much of a good thing. Think about your readership. They don’t want to read another technically proficient paper on Topic X; they want to read something exciting about Topic X. They don’t want to read everything you know about Topic X; they want a good grasp of what it is about Topic X that is important to you. The barbaric butcher knows this, and will therefore consider tearing their text apart into separate papers, each telling a different story in a way that is unique to the individual author.

Let’s say you have three topics to write about: gravity, electricity, and magnetism. Your complete draft is 12,000 words. You may have a better chance publishing at least one paper by dividing the draft into two: a 4,000 word article on gravity, and a 8,000 word article on electromagnetism. Then again, you may decide that the three topics are related enough to be discussed in a single paper. If so, then you may want to cut the 12,000 words down to 9,000, by omitting ideas that are not directly relevant or interesting.

Point being that there are many ways to carve a thesis, and you shouldn’t let your attachment to any part of it impede your commitment to telling a neat, concise story. What you shouldn’t do is take a single topic and data set, and write multiple papers about it, which is a practice known as salami slicing. The barbaric butcher jettisons excess venison; he does not slice salami!

Be alright with what you write

Again, Strunk and White say it best: “If those who have studied the art of writing are in accord on any one point, it is this: the surest way to arouse and hold the reader’s attention is by being specific, definite, and concrete.”

In my own words: do not be precious about your writing. Admittedly, I sometimes do not practice this sermon, but please trust that you will sleep better at night if you do consistently. The butcher should not get attached to the animals, and so we should not be attached to our writing. There is no such thing as the perfect literature review, data collection method, or type of analysis. The theory that you admire and discuss will be the theory that a reader might detest and not want to read about, no matter how technically sound your writing is. You can’t help that. On the other hand, there are infinite ways to construct an argument, so it’s less about choosing the best ways than it is about just committing to some ways, and then refining as best you can.

Choose a suitable design and hold to it.

— William Strunk, Jr., ‘The Elements of Style’, 1919.

Remember to smile in the presence of nihil

In science, the null hypothesis reigns supreme, which means all of our pet theories have a great chance of being wrong anyway! That might sound pessimistic, but I mean it to be pragmatic: when we write, we accept that we are not going to write anything perfect, and put in our best effort all the same.

Of course, we all pray for something positive to write about, like a finding that agrees with our theory and research hypotheses. Although rare, positive findings have the best hopes of being published and generating revenue for scientists. This publication bias affects non-scientists too; I read several books to my toddler night after night, but not one of them describes a scenario where nothing happens, or where the oft-cuddly characters expect nothing to happen.

Positive findings are ideal, but we never should overinflate their apparent validity or importance. Good science is sober science. There’s always a chance that others will expose the carnival mirror reflecting your impossibly thin p-figure.

Negative findings; also known as surprise effects, or those that are opposite of what you hypothesised; are not ideal. Imagine giving an experimental antidepressant to people, only to observe increased measures of depression following the drug’s administration. How do you write about that? The answer is soberly. Smile, but don’t get excited. Breathe. All you need to do is present a case for and against the surprise’s existence. You must be barbarically honest and direct. Avoid the temptation to post-hoc tinker with your analysis or report, and do not scrap the report. You must barbarously sacrifice your own research innocence and dignity so that others do not fall prey to the same surprise you did! Hopefully, you generate enough interest that others replicate your study, to settle more conclusively whether your surprise effect is real or fluke. If the former, then you are cited as the one who discovered it; if the latter, well, you did your job, and one citation is better than none.

Crucially, we never should sweep null findings under the rug. Probability theory implies that most of our results will turn out neither positive nor negative, but null. Rather than finding that Random Factor X decreases (or even increases) depression, we are likely to find that it has no significant bearing on depression levels, given enough randomised trials. Null findings are common because we set the bar high for non-null findings (α ≤ .05). If we were not conservative in this way, then we could claim that just about any finding is not null, but significantly positive (or negative).

Thus, we need to prepare for, practice, and even look forward to reporting such barbarous news to the public and other stakeholders. Null effects may be harder to write about, but they ultimately reward both writer and reader with critical and lateral thinking opportunities. Null findings are excellent proving grounds for the barbaric butcher – report them with too much fatty optimism, and readers will accuse you of bias; too much raw cynicism may prompt readers to question why you bothered in the first place.

The only true “non”-results are results that are so low quality that they are uninformative, either due to poor experimental design or errors in data collection. These failed results may be, on the face of it, either positive or negative.

— Neuroskeptic, ‘Negative Results, Null Results, or No Results?’, 2016.

Summary and next steps

In Part I of this series, the wise warrior was invoked as the essence of living your life while you write. Then, with the Promethean poet, we considered the processes of committing ideas to paper. Together, their actions are additive, suggesting ways to start writing, and to sustain yourself as you make headway.

In contrast, the barbaric butcher is a character with subtractive actions. These actions teach us how to stop writing, which is personally my biggest challenge as a writer. Although it is not always easy poking holes in your own work, the good news is that it becomes more automatic with practice.

Where previously I would lose sleep over losing a paragraph, I am now able to chop first, worry later. After jettisoning my ideas for the day, I don my wise warrior cloak and do something else for a while. I will not look at the manuscript until the next day. After a night of rest, what I usually find is that whatever I dismissed from the manuscript is not missed.

In sum, the trick to stop writing is to stop writhing, and trim the text without personal attachment. Each time you do so, you should reassess with a fresh mind the structure of your text. It is crucial to allow ample time for the adding and taking away cycle. At some point closer to your deadline, you will need to move on from this cycle to the next phase of steps; this I call committing to your audience.

To commit, it is important to realise that the summit is not an end point. This is true in both mountaineering and writing. The writer must anticipate the return journey; this might be dealing with an assignment marker, editor or reviewer, who has made suggestions for improvement. The merciful mercenary is a forecasting expert as you prepare to submit your work, and shall be the topic of Part IV in this series.